Posted on | April 10, 2025 | No Comments

Mike Magee

I. Florence Nightengale and Sidney Herbert

Order had always been part of Florence Nightingale’s life. Her father was William Edward Shore, a Country Squire, who at age 21 inherited his rich uncle’s huge fortune as well as his name. On his death, the younger (now) Nightingale, seamlessly managed the profits of the family’s lead smelting business, as well as, not one, but two named estates – the 1300 acre Lea Hurst in Derbyshire, and the equally impressive Embry Park in Hampshire.

He and his wife had two daughters, each named after the Italian cities where they were born while vacationing. Parthenope carried the Greek name for Naples, and Florence arrived on May 12, 1820, one year later 300 miles north in the “Birthplace of the Renaissance.” The family was well connected with members of Parliament, none closer than Baron Sidney Herbert. It was he who the family turned to for reassurance and guidance when Florence declared at age 16 that her life’s work would be nursing the sick and ill in the service of the Lord.

This was quite a surprise to her father who had taken special care to see that she was classically trained in Greek, Latin, French, German, Philosophy and Religion. But in Florence’s words, she “craved for some regular occupation, for something worth doing instead of frittering away time on useless trifles.” To do so, she was willing to decline suitors and her mother and older sister’s life of comfort and philanthropy.

Sidney Herbert was willing to support the strong willed woman, 10 years his younger, carrying her along on fact-finding trips to Egypt and beyond. None of it shook her commitment. Her intent was clear when she noted in her diary, “On February 7, 1837, God spoke to me and called me to his service.” The calling was specific – nursing the ill in institutional settings. As luck would have it, her goal aligned well with the voluntary efforts of Sidney’s wife, the Lady Elizabeth Mary Herbert, a prodigious fund raiser.

Queen Victoria assumed the throne of England following her Uncle’s death just 4 months after Florence’s religious awakening. The two were born exactly 1 year and 12 days apart. Both the young Queen and her husband, Albert, were military enthusiasts, and saw themselves as active participants in the nation’s armed conflicts. In September, 1854, they had a front row seat in a simmering conflict between the Ottoman Empire and Russia. Britain and France had thought they had brokered a deal between the two primary combatants when the truce fell apart.

Russian Emperor, Nicholas I, then ordered the invasion of what is now current day Romania in July of 1853. By January, 1854, the British and French fleets had entered the Black Sea, and the war was on. Britain’s Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, suggested the effort was preventive. As he said in words that ring true today, “The main and real object of the war is to curb the aggressive ambition of Russia.”

Military historians would later document: “The Crimean War is largely forgotten now, but its impact was momentous. It killed 900,000 combatants; introduced artillery and modern war correspondents to conflict zones; strengthened the British Empire; weakened Russia; and cast Crimea as a pawn among the great powers.”

At the time, Queen Victoria leaned heavily on her new Secretary of War, Sidney Herbert, and Florence Nightingale saw a once in a lifetime opportunity for clinical experience and seized it. With Herbert’s endorsement, she and the 38 nurses in her charge arrived at Barrack Hospital at Scutari, outside modern day Istanbul, ill prepared for the disaster that awaited them. Cholera, dysentery and frostbite – rather than battle wounds – were rampant in the cold, damp, and filthy halls.

During that first winter, 42% of her patients perished, leaving over 4000 dead, the vast majority absent any battle wounds. Florence later described her work setting as “slaughter houses.” Their enemy wasn’t bullets or bayonets, but disease -typhus, cholera and typhoid fever. Over 16,000 British soldiers died, 13,000 from disease.

Nightingale’s initial assessment was that warmer clothing and food would stem the tide. Going over the heads of medical leadership, she did what she could, and leaked details of what she was observing to Herbert and journalists who, for the first time, were stationed within the war zone. In the process, she became a celebrity in her own right, and as Spring of 1855 approached, a first ever Sanitary Commission was sent to the war zone and Victoria and Albert themselves, with two of their children, visited the area.

Famed artist Jerry Barrett made hasty sketches of what would become The Mission of Mercy: Florence Nightingale, which hangs to this day in the National Gallery in London. During this same period, the first lines of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, Santa Filomena, would take shape, including “Lo! In that house of misery, A lady with a lamp I see, Pass through the glimmering of gloom, And flit from room to room.” And the legend of Nightingale, the actual “Lady of the Lamp”, appeared on the front page of the Illustrated London News complete with etched images.

It read: “She is a ministering angel without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides gently along each corridor, every poor fellow’s face softens with gratitude at the sight of her.”

What became clear to Florence and others was that infection and lack of sanitation were the culprits, and corrective actions on the facilities themselves, along with sanitary practices that Nightingale led, caused the subsequent mortality rates to drop to 2%. By the time the war drew to a halt in February, 1856, 900,000 men had died. Florence Nightingale remained for four more months, arriving home without fanfare on July 15, 1856. Thanks to the first ever war correspondents, she was now the 2nd most famous woman in Britain, after Queen Victoria.

While she was away, the Herberts raised money from rich friends. The Nightingale Fund now had 44,000 pounds in reserve. These would help fund a hospital training school and her famous book, “Notes on Nursing” in future years. Though her re-entry was quiet and reserved, she had plenty to say, and committed most of it to writing. While in Crimea, she had written to Britains top statistician, Dr. William Farr. He had replied, “Dear Miss Nightingale. I have read with much profit your admirable observations. It is like light shining in a dark place. You must when you have completed your task – give some preliminary explanation – for the sake of the ignorant reader.” Shortly after her return, they met. Working closely with William Farr, she documented in dramatic form, the deadly toll in Crimea and tied it to disease and lack of sanitation in “Notes Affecting the Health, Efficiency, and Hospital Administration of the British Army”, which she self-published and aggressively distributed.

Illustrated with spin wheel designs divided into 12 sectors, each one representing a month, she graphically tied improved sanitation to plummeting death rates. Understanding their long-term value, she carefully approved the paper, ink, and process that have allowed these images to remain vibrant a century and a half later. As she said later with some cynicism, they were “designed ‘to affect thro’ the Eyes what we may fail to convey to the brains of the public through their word-proof ears.” In 1858, she became the first woman to be made a fellow of the Royal Statistical Society.

In that first year of her return, she was described as “a one woman pressure group and think tank…using statistics to understand how the world worked was to understand the mind of God.”In 1860, she published her “Notes for Nursing,” selling 15,000 copies in first two months. It purposefully championed sanitation (“the proper use of fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet, and the proper selection and administration of diet”) and promoted cleanliness as a path to godliness. It targeted “everywoman” while launching professional nursing.

II. Edwin Chadwick

Florence Nightengale was not the originator of the Sanitary Movement in “Dirty Old London.” That honor goes to one Edwin Chadwick, a barrister who, in 1848, published his “Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Laboring Population of Great Britain.” As historians and commentators have noted, there was a good case to be made for cleanliness. Here are a few of those remarks:

“The social conditions that Chadwick laid bare mapped perfectly onto the geography of epidemic disease…filth caused poverty, and not the reverse.”

“Filthy living conditions and ill health demoralized workers, leading them to seek solace and escape at the alehouse. There they spent their wages, neglected their families, abandoned church, and descended into lives of recklessness, improvidence, and vice.”

“The results were poverty and social tensions…Cleanliness, therefore, exercised a civilizing, even Christianizing, function.”

Chadwick was born on January 24, 1800. His mother died when he was an infant, and his father was a liberal politician and educator. His grandfather was a close confidant of Methodist theologian, John Wesley. Early in his life, young Chadwick pursued a career of his own in law and social reform. A skilled writer, one of his early essays that appeared in the Westminister Review was titled “Applied Science and its place in Democracy.” By the time he was 32, he focused all of expertise on social engineering – especially public health with an emphasis on sanitation

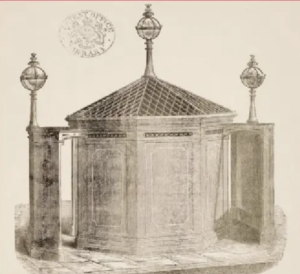

But the Sanitary Movement required population-wide participation, structural change, new technology, and effective story telling. By then, Sir William Harvey’s description of the human circulatory system in 1628, complete with pump, outlet channels, and return venous channels, was well understood by most. Seizing on the analogy, Chadwick, along with city engineers of the day, imagined an underground highway of pipes, to and from every building and home, whose branches, connected to new sanitary devices.

One of those engineers was George Jennings, the owner of South Western Pottery in Dorset, the maker of water closets and sanitary pipes. He was something of a legend in his own time, and recipient of the 1947 Medal of the Society of Arts presented by none other than Prince Albert himself.

When Jennings patented the first toilet, as a replacement for soil pots, hand transported each mornings and emptied in an outhouse if you were lucky, or in the streets if not, its’ future was anything but assured. But, by good luck, the Great Exhibition (the premier display of futuristic visionaries) was scheduled for London in 1851. The Crystal Palace exhibition was the show stopper, attracting a wide range of imagineers. Jennings “Monkey Closet” was the hit of the show. His patent application followed the next year and read: “Patent dated 23 August 1852. JOSIAH GEORGE JENNINGS, of Great Charlotte – street, Blackfriars-road, brass founder. For improvements in water-closets, in traps and valves, and in pumps.”

Modernity had arrived. And none was more enthusiastic than Thomas Crapper, a then 15-year old dreamer. Within three decades he had nine toilet patents, including one for the U-bend, an improvement on the S-bend, and an 1880 Royal commission granted to Thomas Crapper & Co. to install thirty toilets(enclosed and outfitted with cedar wood seats in the newly purchased Norfolk county seat’s Sandringham House. His reputation lives on thanks to this diminutive term, used with the greatest guttural emphasis by the Scots – CRAP. The company is also still in existence, now selling luxury models of the original design.

Sanitary engineering combined with Nightingale’s emphasis on fastidious housekeeping, and cleanliness in hospitals, enforced by nurses with religious zeal, would change the world. And they did. But those same changes would take decades to reach crowded immigrant entry points in locations like New York City.

III. The Horse and Swill Milk

One historian described it this way, “As New York City ascended from a small seaport to an international city in the 1899’s, it underwent severe growing pains. Filth, disease, and disorder ravaged the city to a degree that would horrify even the most jaded modern urban developer.”

One of the prime offenders was the noble work horse. By 1900, on the eve of wholesale arrival of motor cars, there were roughly 200,000 horses in New York City, carrying and transporting humans, and products of every size and shape, day and night along the warn down cobble stone narrow roads and alley ways.

It was a hard life for the horse, who’s lifespan on average was only 2 1/2 years. They were literally “worked to death.” In the 1800’s, 15,000 dead horses were carted away in a single year. Often, they were left to rot in the street because they were too heavy to transport. If they weren’t dying, the horses were producing manure – a startling 5 million pounds dumped on city streets each day.

As for human waste, sewer construction didn’t begin in New York until 1849, this in response to a major cholera outbreak. Clean water had arrived seven years earlier with the arrival Croton Aqueduct carrying water south from Westchester County. This was augmented with rooftop water tanks beginning in 1880. By 1902, most of the city had sewage service including the majority of the tenement houses. The Tenement Act of 1901 had required that each unit have at least one “water closet.”

As for the horses, the arrival of automobiles almost eliminated the “horse problem” overnight. Not so for cows, or more specifically the disease laden “swill milk” cows. Suppliers north of the city struggled to keep up with demand in the late 1800’s. To lower production costs, they fed their cows the cast off “swill” of local alcohol distilleries. This led to infections and a range of diseases in the bargain basement beverage sold primarily to at-risk parents and consumed by children.

Swill milk was the chief culprit in soaring infant mortality in New York City between 1880 and 2000. Annually there were some 150,000 cases of diphtheria, resulting in 15,000 deaths a year. A Swiss scientist, Edwin Klebs, identified the causative bacteria, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, in 1883. A decade later, a German scientist, Emil von Behring, dubbed the “Saviour of Children” developed an anti-toxin to diphtheria and was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1901for the achievement.

The casualties were primarily infants whose mortality rate in NYC at the time was 240 deaths per 1000 live births. Many of these would be traced back to milk infected with TB, typhoid, Strep induced Scarlet Fever and Diphtheria. The casualties were primarily infants whose mortality rate in NYC at the time was 240 deaths per 1000 live births.

The process of heating liquid to purify it, or pasteurization, was discovered by Louis Pasteur in 1856, not with milk but with wine. Its’ use on a broad scale to purify milk first gained serious traction in 1878 after Harper’s Weekly published an expose’ on “Swill Milk.” But major producers and distributors resisted regulation until 1913 when a massive typhoid epidemic from infected milk killed thousands of New York infants. But diphtheria remained the most feared killer of infants.

As Paul DeKruif wrote in his 1926 book, The Microbe Hunters, “The wards of the hospitals for sick children were melancholy with a forlorn wailing; there were gurgling coughs foretelling suffocation; on the sad rows of narrow beds were white pillows framing small faces blue with the strangling grip of an unknown hand.”

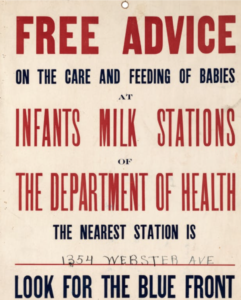

One such victim was the only child of two physicians, Abraham and Mary Putnam Jacobi whose 7-year old son, Ernst, was claimed by the disease in 1883. Working with philathroper, Nathan Straus, the Jacobi’s established pasteurized milk stations in the city which coincided with a 70% decline in infant mortality from diphtheria, tuberculosis and a range of other infectious diseases.

By 1902, the horses hero status was reclaimed as it became the source of diphtheria and tetanus anti-toxins. The bacteria were injected into the horses, and after a number of passes, serum collected from the horse was laden with protective anti-toxins, relatively safe for human use. In 1901 alone, New York City purchased and delivered 25,000 does of ant-toxin funded by the Red Cross and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.